NOTICE: the presence of a topic sentence (with room for improvement, given the content of the paragraph); the citation and explanation of key phrases and words from the text (with half-correct MLA citation: a good effort); and gestures at connections and critical thinking to conclude. This is an above-average paragraph.

We might wish for an explanation of the "their" in the opening sentence, and analysis at the conclusion that goes further than class discussion.

It was the wanting to defend their community that justified their actions. In fact, many embraced the executions of African-Americans and celebrated them in a parade like fashion. This was the case for Henry Smith, who was executed in a similar style. “Arriving here at 10 o’clock the train was met by a surging mass of humanity 10,000 strong. The negro was placed upon his throne, and, followed by an immense crowd, was escorted through the city so that all might see the most inhuman monster known in current history.” (Wells, p. 90) The text mentions the word “monster” which many affiliate with evil. White southerners would use this word to describe African-Americans for their advantage. It allowed them to disguise their actions in terms of their own victimization. Therefore, many white southerners did not believe what they were doing was wrong. “Curiosity seekers have carried away already all that was left of the memorable event, even a piece of charcoal.” (Wells, p. 91) The crowd gives off a sporting event feel by illustrating the crowds’ willingness to cling on to artifacts for memorabilia; similar to a fan at a baseball game who hopes to catch a ball. I feel this literature piece is more detailed and illustrates a lynching on a grander scale in comparison to a silent film.

Dr. Justin Rogers-Cooper's ENN 195 urban studies course, "Violence in American Art and Literature."

Monday, January 30, 2012

Model Opening Paragraph: Assignment One

NOTICE: opening scene, transition to texts under discussion, specific thesis statement.

Perhaps Jube never had the guarantee of living out his life to its entirety and even less one with out the possibility of being mistreated by his fellow man. Still, the fate that he was dealt with was depicted by Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s short story The Lynching of Jube Benson was lawless, humiliating and brute. Begging for his life and questioning his own likelihood in the murder for which he was accused, had spared him no mercy. He was quickly taken by a crazed mob led by a local doctor and friend no less, hung before a crowd moments before his brother Ben and a friend brought the actual culprit to the anxious and grotesquely motivated crowd. The written accounts of the unjust murder of Jube Benson were extensively more graphic than that of any visually violent scene. The film Within Our Gates portrays an equally vile crime, a sexual assault attempt. The visual advantage of this medium may be limited only by the scenes provided in the film. A written chronicle of either of these crimes in my opinion has the greater advantage at arousing an emotional response from perceiver as they are hindered not by the imagination of a film director. Written literature of violence can be extensively more vivid by illustrating the emotion with unique detailed accuracy.

Perhaps Jube never had the guarantee of living out his life to its entirety and even less one with out the possibility of being mistreated by his fellow man. Still, the fate that he was dealt with was depicted by Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s short story The Lynching of Jube Benson was lawless, humiliating and brute. Begging for his life and questioning his own likelihood in the murder for which he was accused, had spared him no mercy. He was quickly taken by a crazed mob led by a local doctor and friend no less, hung before a crowd moments before his brother Ben and a friend brought the actual culprit to the anxious and grotesquely motivated crowd. The written accounts of the unjust murder of Jube Benson were extensively more graphic than that of any visually violent scene. The film Within Our Gates portrays an equally vile crime, a sexual assault attempt. The visual advantage of this medium may be limited only by the scenes provided in the film. A written chronicle of either of these crimes in my opinion has the greater advantage at arousing an emotional response from perceiver as they are hindered not by the imagination of a film director. Written literature of violence can be extensively more vivid by illustrating the emotion with unique detailed accuracy.

Blog Assignment FIVE: Mosley's Little Scarlet

Please select one of the themes we've been discussing in class and explore it in a close-reading of a passage from the text. Your blog should go further than class discussion, and focus on explaining what scenes, images, words, and actions mean. Strike to make connections between the passage and larger issues we've discussed in class.

Please note that all the powerpoints are now available on the course's blackboard site.

Please note that all the powerpoints are now available on the course's blackboard site.

1943 Harlem and 1965 Watts

In class Monday we discussed Ann Petry's In Darkness and Confusion, and in class Thursday we discussed the opening chapters of Walter Mosley's Little Scarlet.

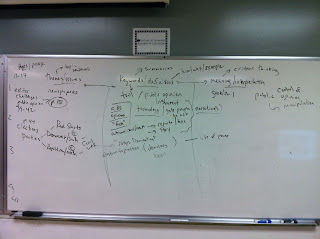

In class Monday we discussed Ann Petry's In Darkness and Confusion, and in class Thursday we discussed the opening chapters of Walter Mosley's Little Scarlet.The discussion of the Petry short story was spread through four groups; each group focused on a different theme from the text: education, the riot, the protagonist William's relationship to his son, Sam, and the impact of World War II on the events in the text. As we observed from our power point during class, the contradictions of the war and pervasive discrimination through defense industries had provided some of the background context for the riot. We also closely examined the connections between high wartime food prices, resentments against police brutality, and poor living conditions in Harlem. Students can check their notes against the notes on the board accompanying this post. They should note, too, that we covered some of the big themes that have been raised thus far in the course.

In Thursday's class we learned more about Watts and theories of "hostile belief systems" and the role they play in riots. We looked at those ideas from Terry Ann Knopf's Rumor Race and Riot, and then initiated a discussion of Mosley's Little Scarlet. Perhaps most notably, we framed our discussion using the opening scene, post-riot, when Easy Rawlins speaks to a disgruntled customer at a burned out shoe store. The customer had been desiring "justice" in a larger sense, not just the price of his lost shoes. As he Easy moved into his investigation of Nola Payne (and the central theme of black women comes into focus), his ability to move between different neighborhoods and spaces becomes important. He also must 'control' his behavior in order to keep his focus on the job. We moved this language of nerves and pulses into a more general discussion about the way trauma and emotion become biologized in the body - the 'self' is not 'one' with the body.

In Thursday's class we learned more about Watts and theories of "hostile belief systems" and the role they play in riots. We looked at those ideas from Terry Ann Knopf's Rumor Race and Riot, and then initiated a discussion of Mosley's Little Scarlet. Perhaps most notably, we framed our discussion using the opening scene, post-riot, when Easy Rawlins speaks to a disgruntled customer at a burned out shoe store. The customer had been desiring "justice" in a larger sense, not just the price of his lost shoes. As he Easy moved into his investigation of Nola Payne (and the central theme of black women comes into focus), his ability to move between different neighborhoods and spaces becomes important. He also must 'control' his behavior in order to keep his focus on the job. We moved this language of nerves and pulses into a more general discussion about the way trauma and emotion become biologized in the body - the 'self' is not 'one' with the body. Students should note, too, that we discussed the second assignment on Thursday. Some of the vital issues students might consider for their writing are noted in the board notes here.

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

Economy and Riots

George Soros - an advisor to Obama, and one of the richest men in the world, predicts urban riots. Check the link HERE.

Monday, January 23, 2012

Videos: World War II Context for 1943 Harlem Riots

Video: from The War: Segregation, Its Impact

http://www.pbs.org/thewar/detail_5381.htm

Video: from The War: African-American Troop Training

http://www.pbs.org/thewar/detail_5373.htm

http://www.pbs.org/thewar/detail_5381.htm

Video: from The War: African-American Troop Training

http://www.pbs.org/thewar/detail_5373.htm

Depression and Race Riots

Last week we hovered in the first few decades of the 20th century, and examined race riots and the Great Depression. To do this we looked through the lens of two novels: Nathaniel West's The Day of the Locust and David Bryant Thorne's Hanover, Or the Persecution of the Lowly. In both novels, we see an intersection between collective violence, collective resentment, and collective aggression against bodies that are simultaneously symbolic and objective targets of that violence.

Last week we hovered in the first few decades of the 20th century, and examined race riots and the Great Depression. To do this we looked through the lens of two novels: Nathaniel West's The Day of the Locust and David Bryant Thorne's Hanover, Or the Persecution of the Lowly. In both novels, we see an intersection between collective violence, collective resentment, and collective aggression against bodies that are simultaneously symbolic and objective targets of that violence.When we watched the final scene of John Schlesinger's 1975 vision of The Day of the Locust, for example, we clearly see the way the enraged crowd gathered for a Hollywood film premiere quickly turns on the very symbols and bodies of its affection. Once the destruction begins, the symbols of wealth, status, and power immediately become targets for resentment, frustration, and rage. This occurs even as the crowd turns on itself, particularly in form of older men devouring young children. The crowd eats its young - just as Hollywood exploits crowds through it's "dream dump" of historical and romantic fantasies. American life was so many groups and classes feeding off one another; The Day of the Locust, I argued somewhat playfully, is the first zombie text.

Later in the week, we returned to earlier moments of the 20th century in order to revisit another form of racial violence that emerged out of white supremacy and American nationalism (besides lynching): the race riot. Like lynching, race riots involved some narrative of sexual violation between white and black communities. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of those sexual violation narratives were produced, circulated, and sustained by the authority of newspapers. In the case of Hanover, we find that the entire riot of Wilmington, North Carolina was planned by local Democrats in order to return to power. They used the newspaper as an agent instigation and accusation, but the execution involved to overthrow black and Republican government took months to organize and involved several different kinds of figures in the white community. We conversed about how elite members of the white community were able to mobilize lower-class whites as a militant "Red Shirt" organization through narratives of sexual violation, but also through promises of material gain.

Later in the week, we returned to earlier moments of the 20th century in order to revisit another form of racial violence that emerged out of white supremacy and American nationalism (besides lynching): the race riot. Like lynching, race riots involved some narrative of sexual violation between white and black communities. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of those sexual violation narratives were produced, circulated, and sustained by the authority of newspapers. In the case of Hanover, we find that the entire riot of Wilmington, North Carolina was planned by local Democrats in order to return to power. They used the newspaper as an agent instigation and accusation, but the execution involved to overthrow black and Republican government took months to organize and involved several different kinds of figures in the white community. We conversed about how elite members of the white community were able to mobilize lower-class whites as a militant "Red Shirt" organization through narratives of sexual violation, but also through promises of material gain.As in later race riots in Atlanta and Tulsa, the Wilmington riot coalesced white civic passions around the threat of black masculinity, but we cannot explain the riot without understanding how certain members of the crowd stood to gain from its activities. In order to understand the anatomy of the crowd, then, we have to locate how it's formed and how it acts according to a certain logic. It's not a simple "destruction," as Le Bon might put it, but a focused violence that reconfigures local political and economic order for the gain of particular members of the community. Everyone stands something to gain, but each gains something different: the Democrat leaders re-assume power and re-assign black jobs to favored white persons; opportunistic or organized members of the white community can take over black homes and businesses, and thus appropriate wealth and status; and exploited members of the white community can assign blame and punish others for their condition in life, without having to blame themselves or, somewhat impossibly, members of the white elite. Taken together, these actions are more economically and politically strategic than abjectly destructive. The economist David Harvey calls these moments of organized mass theft "accumulation by dispossession."

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Link to Zizek

Daniel brought in this link to Zizek talking about memory and trash. We didn't have time to talk about it in class. Here's the link (thanks Daniel):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGCfiv1xtoU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGCfiv1xtoU

Dunbar's Jube Benson and Griffith's Birth of a Nation

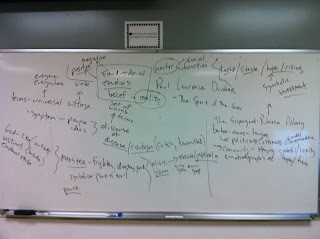

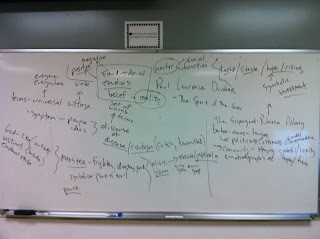

In class Thursday we went over two of Paul Lawrence Dunbar's short stories: "The Scapegoat" and "The Lynching of Jube Benson," both from his collection The Heart of Happy Hollow, published in 1904. After the break, we watched some of the key clips from D.W. Griffith's blockbuster The Birth of a Nation (1915).

Before we began looking at the stories, we read over the preface from Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd, first published in France in 1896 and translated into English the following year. We discussed how Le Bon considered the crowd a threatening collection of urban masses, who were bent on organizing themselves into unions and demanding suffrage. He contrasted these self-determining rights of the crowd with his stance that crowds were built for destruction, could not reason, and appeared when "civilizations" were in their collapse.

Before we began looking at the stories, we read over the preface from Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd, first published in France in 1896 and translated into English the following year. We discussed how Le Bon considered the crowd a threatening collection of urban masses, who were bent on organizing themselves into unions and demanding suffrage. He contrasted these self-determining rights of the crowd with his stance that crowds were built for destruction, could not reason, and appeared when "civilizations" were in their collapse.

In Dunbar's story "Scapegoat," the class made a number of interesting observations. The main character, Robinson Asbury, had a special relationship to his black community because he remained in the neighborhood of 'the people' even as his success as a barber and then as a lawyer could have allowed him to taken off to better streets. He decides to enter politics, and a clique of the town's old guard prevents him by nominating a stooge candidate, a local school principal, to compete against him. He cannot raise as many people in an annual parade, however, which portends he won't be able to raise votes. After Asbury wins the election, the group backing the principal (Morton) cries "fraud," and the old guard are only too happy to see the election battle go to trial. Here, the class made much of the fact that Dunbar explains the cries of "fraud" as protests by those that had ulterior emotional motives. We played this into a conversation that shuffled around the ways emotion and belief are tied together, and how people with emotional investments can refuse to believe in reality if it doesn't fit their emotional paradigm. For many, Asbury was a symbol and a model for them. He embodied their hopes. For others he was the opposite.

In Dunbar's story "Scapegoat," the class made a number of interesting observations. The main character, Robinson Asbury, had a special relationship to his black community because he remained in the neighborhood of 'the people' even as his success as a barber and then as a lawyer could have allowed him to taken off to better streets. He decides to enter politics, and a clique of the town's old guard prevents him by nominating a stooge candidate, a local school principal, to compete against him. He cannot raise as many people in an annual parade, however, which portends he won't be able to raise votes. After Asbury wins the election, the group backing the principal (Morton) cries "fraud," and the old guard are only too happy to see the election battle go to trial. Here, the class made much of the fact that Dunbar explains the cries of "fraud" as protests by those that had ulterior emotional motives. We played this into a conversation that shuffled around the ways emotion and belief are tied together, and how people with emotional investments can refuse to believe in reality if it doesn't fit their emotional paradigm. For many, Asbury was a symbol and a model for them. He embodied their hopes. For others he was the opposite.

Asbury can't defend the corruption of the vote, apparently, but during the trial exposes the rest of the political machinery as just as guilty as he. He goes to jail for a year and comes out stronger; from that point forward, his status among the people as a martyr allows him to influence local town politics from behind the scenes.

Before we began looking at the stories, we read over the preface from Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd, first published in France in 1896 and translated into English the following year. We discussed how Le Bon considered the crowd a threatening collection of urban masses, who were bent on organizing themselves into unions and demanding suffrage. He contrasted these self-determining rights of the crowd with his stance that crowds were built for destruction, could not reason, and appeared when "civilizations" were in their collapse.

Before we began looking at the stories, we read over the preface from Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd, first published in France in 1896 and translated into English the following year. We discussed how Le Bon considered the crowd a threatening collection of urban masses, who were bent on organizing themselves into unions and demanding suffrage. He contrasted these self-determining rights of the crowd with his stance that crowds were built for destruction, could not reason, and appeared when "civilizations" were in their collapse. In Dunbar's story "Scapegoat," the class made a number of interesting observations. The main character, Robinson Asbury, had a special relationship to his black community because he remained in the neighborhood of 'the people' even as his success as a barber and then as a lawyer could have allowed him to taken off to better streets. He decides to enter politics, and a clique of the town's old guard prevents him by nominating a stooge candidate, a local school principal, to compete against him. He cannot raise as many people in an annual parade, however, which portends he won't be able to raise votes. After Asbury wins the election, the group backing the principal (Morton) cries "fraud," and the old guard are only too happy to see the election battle go to trial. Here, the class made much of the fact that Dunbar explains the cries of "fraud" as protests by those that had ulterior emotional motives. We played this into a conversation that shuffled around the ways emotion and belief are tied together, and how people with emotional investments can refuse to believe in reality if it doesn't fit their emotional paradigm. For many, Asbury was a symbol and a model for them. He embodied their hopes. For others he was the opposite.

In Dunbar's story "Scapegoat," the class made a number of interesting observations. The main character, Robinson Asbury, had a special relationship to his black community because he remained in the neighborhood of 'the people' even as his success as a barber and then as a lawyer could have allowed him to taken off to better streets. He decides to enter politics, and a clique of the town's old guard prevents him by nominating a stooge candidate, a local school principal, to compete against him. He cannot raise as many people in an annual parade, however, which portends he won't be able to raise votes. After Asbury wins the election, the group backing the principal (Morton) cries "fraud," and the old guard are only too happy to see the election battle go to trial. Here, the class made much of the fact that Dunbar explains the cries of "fraud" as protests by those that had ulterior emotional motives. We played this into a conversation that shuffled around the ways emotion and belief are tied together, and how people with emotional investments can refuse to believe in reality if it doesn't fit their emotional paradigm. For many, Asbury was a symbol and a model for them. He embodied their hopes. For others he was the opposite. Asbury can't defend the corruption of the vote, apparently, but during the trial exposes the rest of the political machinery as just as guilty as he. He goes to jail for a year and comes out stronger; from that point forward, his status among the people as a martyr allows him to influence local town politics from behind the scenes.

Thursday, January 12, 2012

Class Notes on Lynching: "A Red Record" and "Within Our Gates"

Monday's class covered assigned excerpts from Ida B. Well's A Red Record and Oscar Micheaux's film Within Our Gates.

A Red Record

The class summarized from Well's Red Record that the three main excuses given by white southerners for lynching were "Negro Domination" (political power), suppression of race riots, and rape. The class noted that each of these reasons was based on fear of black persons, and even of black men in particular. We also noted that it was important that white southerners constantly framed their actions in terms of their own victimization. It was their "defense" of their community that justified their actions. They didn't see themselves as bad guys.

The class summarized from Well's Red Record that the three main excuses given by white southerners for lynching were "Negro Domination" (political power), suppression of race riots, and rape. The class noted that each of these reasons was based on fear of black persons, and even of black men in particular. We also noted that it was important that white southerners constantly framed their actions in terms of their own victimization. It was their "defense" of their community that justified their actions. They didn't see themselves as bad guys.

We had to reckon this reasoning with the actual sport-appeal of lynchings themselves, in which the class agreed the white southerners took an obvious pleasure. This pleasure was sadistic: it was a pleasure that came from the spectacle of suffering. As we read over selected passages from A Red Record about the lynching of Henry Smith in Paris, Texas, in 1893, the class argued that the parade and gathered thousands was an event that demonstrated that tolerance for certain kinds of violence is learned social behavior. The enjoyment felt by the south might be awful to us, but it was a product of the era. We didn't let the matter rest there, however; we did note that the lynchers inability to "see" the extremity of their violence came from an "ideological" blindness. The violence that occurs without question is violence that has been fully integrated into a worldview. We debated briefly what forms of violence that occurs today that might appear heinous to the future, such as the death penalty.

Within Our Gates

In Oscar Micheaux's film Within Our Gates (1920), we watched the school teacher Sylvia Landry head north to Boston from the south to secure funding for southern black schools. In the north, we witness Sylvia head to the home of rich Bostonian woman and ask for money; the woman debates the matter with her southern friend, who argues against Negro education. While there, she meets one Dr. Vivian, a black intellectual, and they fall in love.

In one interesting scene, a gambler named Larry Prichard (brother of Sylvia's friend Alma) has a shoot-out with his mate Red. He's chased by the detective Phillip Gentry.

We learn that in the past Sylvia's family was lynched by a southern mob bent on punishing her father for an accused murder of a leading white plantation owner, Phillip Gridlestone. In reality, Gridlestone was shot by an angry white worker. When Gridlestone's son comes to rape and probably murder Sylvia during the lynching, he finds a scar on her chest that reveals her as his long lost sister - Sylvia is "white." She returns to Boston to be with Dr. Vivian.

We focused on the lynching scene in particular. The black character Efrem is lynched first, before the mob can find the Landry family. The family is then lynched upon their discovery, although their youngest son escapes and flees on a horse.

Please check my plot notes against the summary HERE.

A Red Record

The class summarized from Well's Red Record that the three main excuses given by white southerners for lynching were "Negro Domination" (political power), suppression of race riots, and rape. The class noted that each of these reasons was based on fear of black persons, and even of black men in particular. We also noted that it was important that white southerners constantly framed their actions in terms of their own victimization. It was their "defense" of their community that justified their actions. They didn't see themselves as bad guys.

The class summarized from Well's Red Record that the three main excuses given by white southerners for lynching were "Negro Domination" (political power), suppression of race riots, and rape. The class noted that each of these reasons was based on fear of black persons, and even of black men in particular. We also noted that it was important that white southerners constantly framed their actions in terms of their own victimization. It was their "defense" of their community that justified their actions. They didn't see themselves as bad guys.We had to reckon this reasoning with the actual sport-appeal of lynchings themselves, in which the class agreed the white southerners took an obvious pleasure. This pleasure was sadistic: it was a pleasure that came from the spectacle of suffering. As we read over selected passages from A Red Record about the lynching of Henry Smith in Paris, Texas, in 1893, the class argued that the parade and gathered thousands was an event that demonstrated that tolerance for certain kinds of violence is learned social behavior. The enjoyment felt by the south might be awful to us, but it was a product of the era. We didn't let the matter rest there, however; we did note that the lynchers inability to "see" the extremity of their violence came from an "ideological" blindness. The violence that occurs without question is violence that has been fully integrated into a worldview. We debated briefly what forms of violence that occurs today that might appear heinous to the future, such as the death penalty.

Within Our Gates

In Oscar Micheaux's film Within Our Gates (1920), we watched the school teacher Sylvia Landry head north to Boston from the south to secure funding for southern black schools. In the north, we witness Sylvia head to the home of rich Bostonian woman and ask for money; the woman debates the matter with her southern friend, who argues against Negro education. While there, she meets one Dr. Vivian, a black intellectual, and they fall in love.

In one interesting scene, a gambler named Larry Prichard (brother of Sylvia's friend Alma) has a shoot-out with his mate Red. He's chased by the detective Phillip Gentry.

We learn that in the past Sylvia's family was lynched by a southern mob bent on punishing her father for an accused murder of a leading white plantation owner, Phillip Gridlestone. In reality, Gridlestone was shot by an angry white worker. When Gridlestone's son comes to rape and probably murder Sylvia during the lynching, he finds a scar on her chest that reveals her as his long lost sister - Sylvia is "white." She returns to Boston to be with Dr. Vivian.

We focused on the lynching scene in particular. The black character Efrem is lynched first, before the mob can find the Landry family. The family is then lynched upon their discovery, although their youngest son escapes and flees on a horse.

Please check my plot notes against the summary HERE.

Monday, January 9, 2012

Blog Assignment Two

For their second blog, students should reflect on some of Zizek's terms for violence, and then meditate on the photographs of lynching we observed in class. Are the lynchings examples of subjective or objective violence? What was the purpose of the violent lynchings? Why were they so popular? What was their connection to "punishment"? What do they say about racial identity in the US in the 19th century? Students may frame their thoughts and reactions however they wish, as they long as they write with these questions and terms in mind. Students are especially encouraged to create new arguments and vocabulary for themselves.

Theories of Violence: terms from Zizek

subjective violence: violence performed by a clearly identifiable agent

symbolic violence: violence embodied in language and its forms

systemic violence: the violence and routine consequences of the smooth functioning of economic and political systems

"Subjective violence is experienced as such against the background of a non-violent zero level. It is seen as a perturbation of the "normal," peaceful state of things. However, objective violence is invisible since is sustains the very zero-level standard against which we perceive something as subjectively violent" (Zizek 2).

"There is something inherently mystifying in a direct confrontation with [violence]: the over-powering horror of violent acts and empathy with the victims inexorably function as a lure which prevents us from thinking" (Zizek 4).

"Reality": is the social reality of the actual people involved in interaction and in the productive processes, while the Real is the inexorable "abstract," spectral logic of capital that determines what goes on in social reality" (Zizek 13)

Objective violence is always accompanied by a "subjective" excess: "the irregular, arbitrary exercise of whims. An exemplary case of this interdependence is provided by Etienne Balibar, who distinguishes two opposite but complementary modes of excessive violence: the "ultra-objective" or systemic violence that is inherent in the social conditions of global capitalism, which involve the "automatic" creation of excluded and dispensable individuals from the homeless to the unemployed, and the "ultra-subjective" violence of newly emerging ethnic and/or religious, in short racist, "fundamentalisms" (Zizek 14).

symbolic violence: violence embodied in language and its forms

systemic violence: the violence and routine consequences of the smooth functioning of economic and political systems

"Subjective violence is experienced as such against the background of a non-violent zero level. It is seen as a perturbation of the "normal," peaceful state of things. However, objective violence is invisible since is sustains the very zero-level standard against which we perceive something as subjectively violent" (Zizek 2).

"There is something inherently mystifying in a direct confrontation with [violence]: the over-powering horror of violent acts and empathy with the victims inexorably function as a lure which prevents us from thinking" (Zizek 4).

"Reality": is the social reality of the actual people involved in interaction and in the productive processes, while the Real is the inexorable "abstract," spectral logic of capital that determines what goes on in social reality" (Zizek 13)

Objective violence is always accompanied by a "subjective" excess: "the irregular, arbitrary exercise of whims. An exemplary case of this interdependence is provided by Etienne Balibar, who distinguishes two opposite but complementary modes of excessive violence: the "ultra-objective" or systemic violence that is inherent in the social conditions of global capitalism, which involve the "automatic" creation of excluded and dispensable individuals from the homeless to the unemployed, and the "ultra-subjective" violence of newly emerging ethnic and/or religious, in short racist, "fundamentalisms" (Zizek 14).

Thursday, January 5, 2012

The Civil War Draft Riots

Our class on Thursday began to discuss the different factors that motivate mass social violence by examining the 1863 Civil War Draft Riots. We learned about the riots from the PBS "New York" (2004) DVD "Order and Disorder," and we also looked at a few scenes from Martin Scorsese's The Gangs of New York (2003). Besides observing that New York in the 1850s and into the Civil War was generally a violent place, we also noted that many of the issues that make the United States a place called "America" also arose in the film - namely, the US is a place where the fiction of the American Dream rises and falls against a tide of immigrant and "native" expectations and feelings.

In the Draft Riots, for example, the overwhelming participation of the Irish working class wasn't coincidental. Even though new Irish immigrants had taken jobs from African-Americans in the preceding decades, as the PBS documentary points out, they were afraid that free African Americans - and newly freed slaves in particular -- were going to take their jobs. Democrat politicians like Mayor Fernando Wood helped activate those fears through excited warnings about the dangers of free black Americans.

The class was quick to point out, however, that Irish fears about their economic security and about work competition also took place in the context of virulent white supremacist culture. The Irish wanted to be white, and not just because of the advantages it conferred. Status as white individuals - as white men, in particular -- would mean that the Irish could gain an easier path to economic and political "rights" (indeed, one point that the PBS film makes clear is that the Irish were taken much more seriously as a political class after the riots).

The Draft Riots also allowed the class to reach back into the founding documents of American national identity: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. We spent some time unpacking just what "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" meant, and how that final idea, happiness, may have had something to do with the aforementioned American Dream. We also noted that the Declaration of Independence moves from an assertion of natural rights from God in the first paragraph to an assertion of rights as "people" in the second paragraph. In short, power moves from a higher power than a King to a power justified by the desires of a collective group. This change transforms once more in Article One, Section Two of the Constitution, which introduces the idea of "free persons" as another category of citizenship for American nationality. As Anibal pointed out, two documents that he thought were positive, celebratory texts also contain the ideas that sustained different forms of civil violence in the US. The Constitution, with its 3/5 clause for counting slaves, embedded the idea of racial inequality into US legal identity. The groundwork for the Civil War thus appears there -- just as the immigrant-oriented American Dream appears in the Declaration of Independence, even though the document also appears to invent a general theory of rebellion against all forms of power.

Declaration photo from archives.gov

In the Draft Riots, for example, the overwhelming participation of the Irish working class wasn't coincidental. Even though new Irish immigrants had taken jobs from African-Americans in the preceding decades, as the PBS documentary points out, they were afraid that free African Americans - and newly freed slaves in particular -- were going to take their jobs. Democrat politicians like Mayor Fernando Wood helped activate those fears through excited warnings about the dangers of free black Americans.

The class was quick to point out, however, that Irish fears about their economic security and about work competition also took place in the context of virulent white supremacist culture. The Irish wanted to be white, and not just because of the advantages it conferred. Status as white individuals - as white men, in particular -- would mean that the Irish could gain an easier path to economic and political "rights" (indeed, one point that the PBS film makes clear is that the Irish were taken much more seriously as a political class after the riots).

The Draft Riots also allowed the class to reach back into the founding documents of American national identity: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. We spent some time unpacking just what "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" meant, and how that final idea, happiness, may have had something to do with the aforementioned American Dream. We also noted that the Declaration of Independence moves from an assertion of natural rights from God in the first paragraph to an assertion of rights as "people" in the second paragraph. In short, power moves from a higher power than a King to a power justified by the desires of a collective group. This change transforms once more in Article One, Section Two of the Constitution, which introduces the idea of "free persons" as another category of citizenship for American nationality. As Anibal pointed out, two documents that he thought were positive, celebratory texts also contain the ideas that sustained different forms of civil violence in the US. The Constitution, with its 3/5 clause for counting slaves, embedded the idea of racial inequality into US legal identity. The groundwork for the Civil War thus appears there -- just as the immigrant-oriented American Dream appears in the Declaration of Independence, even though the document also appears to invent a general theory of rebellion against all forms of power.

Declaration photo from archives.gov

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)